Three Things I Learned from 100 Story Sales

Posted on January 30, 2026 by Aeryn Rudel

Since I started submitting work seriously in 2013, I’ve sold* 120 short stories. Like the piles of rejections I’ve racked up in that same time, my much smaller heap of acceptances has taught me some valuable lessons about writing and the often arcane process of trying to get other people to publish your work. Let’s talk about three of them.

- Short Sells. In my experience, the shorter the story, the easier it is to sell. I even have stats to back it up. To date, I have sold 85 flash fiction stories and 29 short stories. I’ve also sold a novella and a handful of micros, but, you know, sample size. It generally takes me about three submissions to sell a flash piece, while it takes an average of eight to sell a short story. Part of this might simply be because I’m better at writing flash fiction than I am at writing longer works, but there are definitely other factors at play. One, flash fiction markets tend to publish more often, sometimes once per week, hell, sometimes daily, so they tend to be open to subs more often and they need more subs than other journals. So, basically, your chances of selling a flash piece are just better because there are more open slots. Now, this is not to say you shouldn’t write and submit shorts–I mean, I do–but you should expect it to take a little longer to get stories over 1,000 words accepted. Of course, this could just be a me problem, and the rest of you are selling 5,000-word shorts on the first sub. 🙂

- Dance With the Ones That Brung Ya. Look, I definitely try to sell as many stories to as many markets as possible, but when I find a publisher that likes my work enough to publish it multiple times and pays a pro rate, I’m going back to that well. A LOT. You see, I am convinced that selling a story comes down to right editor, right time, right place, and when I sell multiple pieces to the same market, then I feel I’ve got two of those things in my favor. It’s even better when these markets that get me are pro rate publishers. So, yes, I’m gonna keep chasing acceptances at Flash Fiction Online, Small Wonders, Nightmare, and Apex, but I’m also gonna keep sending stories to Factor Four Magazine, MetaStellar, and The Flame Tree Flash Fiction Newsletter, all of which have published me three or more times. It’s good for my acceptance numbers, good for my confidence, and it puts more of my stories at respected markets for folks to read.

- It’s Okay to Ignore Editorial Feedback. Getting feedback on a rejection is great, and I have nothing but gratitude for editors that take the time to leave a personal note. For one, it tells you a lot about what the editor wants out of a story, and it can tell you when it’s time to revise. That said, a lot of feedback is simply editorial preference, and it’s perfectly okay to ignore it if it doesn’t fit your vision of the story. I’ve received feedback on stories that were rejected, decided not to action that feedback, and then sold the story to a pro market on the next submission. Conversely, I have taken editorial feedback to heart when it resonated with me, made the revisions, and then sold the story likely because of those revisions. This is not to say that the editorial feedback I ignore is wrong. It’s 100% right for that editor and that market, but ultimately not right for my story. It can be tricky to tell which is which of course, and it comes down to a gut feeling borne out of experience and a deep understanding of your specific goals with each story.

So, there you have it. Three lessons learned from 100-plus story sales. Now, admittedly, these are fairly specific to my personal experiences, but I think there’s some universal truths here that are applicable to anyone heading into the submission trenches.

What have you learned from your own story sales? I’d love to hear about it in the comments.

*The vast majority of my short story publications are of the paid variety, but for the sake of transparency, there are some “for the love of it” publications in the mix.

2026 Writing Goals Bingo

Posted on January 15, 2026 by Aeryn Rudel

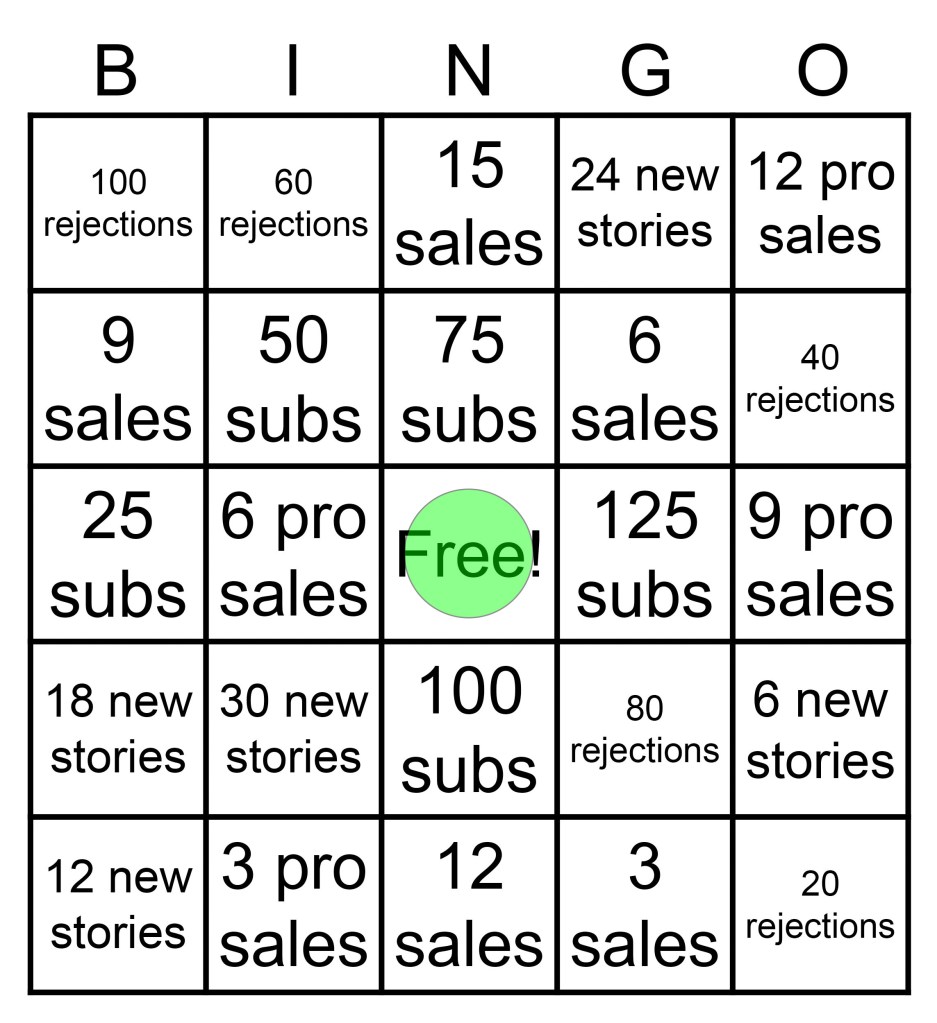

Last year, I set a number of short fiction writing goals for myself that I represented in a bingo card as a fun bit of motivation and to have a snazzy graphic for blog posts. Though, at the end of the year, I did okay, I may have been a little too ambitious. Anyway, I’m doing the writing goals bingo thing again for 2026, but I’m being a tad more conservative with how high I set the bar in certain areas. So, without further ado, here’s the 2026 goals.

So, the five goals, which are each broken up into five sperate tiers above, are:

- 120 Submissions

- 100 Rejections

- 15 Acceptances

- 12 Pro Sales

- 30 New Stories

Each of the goals is pretty straight forward, but I’ll discuss each one and give you my reasoning for where I set the bar.

120 Submissions – Last year, I set this goal at 150, and I managed 122 submissions. I’m setting it at 120 this year because though it is a very steady pace, it’s not breakneck. That said, this is one of the goals I think I can easily hit or exceed since it’s entirely within my control.

100 Rejections – For me, hitting 100 rejections means I’m a) sending a lot of submissions and b) writing a lot of new material. So, it’s kind of gauge for how I’m doing other goals, and if I hit those, I should hit this one almost by default.

15 Acceptances – In 2025, I set this mark at 25 acceptances, which is, admittedly, bananas. I don’t regret doing it since I have flirted with 20 acceptances in a single year in the past, but in the current literary environment, and since I primarily submit to pro markets, 15 feels a lot more doable, and, hey, I WANT to succeed. 😉

12 Pro Sales – This is probably the most ambitious of my goals, as pro sales are pretty tough to come by. Last year, I had five pro sales, which was half of my ten total. I did, however, have A LOT of final-round rejections from pro markets, so I feel like ten or twelve is possible with a little luck. So, yeah, twelve is ambitious, but I think doable.

30 New Stories – Last year, I set another ambitious writing goal, which was to write a new story every week. I didn’t succeed, but I did manage 35 new stories, which is a good number, I think. I set the bar a little lower this year because I’ve got some other projects I want to work on. But if I can manage 30 new stories, I should have pretty good shot at hitting my other goals.

And those are my short story submission goals for 2026. Although I backed off a bit from last year’s goals, I think these are more than respectable, and if I can hit them all, that’ll be a hell of a good year.

What are your writing goals in 2026? I’d love to hear about them in the comments.

What Happens to Rejected Stories?

Posted on January 12, 2026 by Aeryn Rudel

Recently, it came to my attention that when I say “I have almost 800 rejections”, some folks think YOU’VE HAD 800 STORIES REJECTED?! That’s understandable without context, especially if you’re not in the biz. It did get me thinking, though. Just how many distinct stories have I had rejected? And, further, what happened to those stories? Let’s find out!

To date, I have 773 rejections since I started tracking them back in 2012. I ran a quick report on Dutrope, and those 773 rejections equate to 166 distinct pieces. Most of those pieces are flash fiction and short stories, but there’s a novella and a couple of novels mixed in there, too.

Looking deeper, here’s what happened to those 166 rejected stories.

- Accepted: 87 (418)

- Pending/Potential: 27 (182)

- Trunked: 52 (173)

I’ve broken the rejected stories into three broad categories with the number of stories and the total number of rejections each category is responsible for. Let’s drill down, and I’ll explain what each category means.

Accepted

Pretty straight forward. The stories in this category, despite racking up a ton of rejections, were eventually accepted and published somewhere. They constitute a full 54% of my rejections, which, honestly, makes me feel pretty good and definitely says something about sticking with stories you feel confident about even thought they’re getting rejected. In fact, thirty of these stories received five or more rejections and fourteen of them suffered through double digits. Persistence for the win, huh?

Pending/Potential

The twenty-seven stories in this category are either currently pending with a publisher, or they’re stories I think are good enough to keep sending out. Most are fairly recent pieces, but there’s a couple of veterans in here with over twenty rejections that I keep doggedly submitting. It’s possible and even likely that some of these stories will eventually be relegated to the next category.

Trunked

If you’re unfamiliar with this term, trunked simply means when an author has given up on publishing a story, generally because they’ve decided it’s just not good enough. Most of the fifty-two stories in this category are pretty old, originating in the early 2010s when I first started submitting seriously. There’s not very many recent stories in here, mostly because I’ve gotten better at identifying pieces that are just not gonna sell before I start submitting them. That said, I have on occasion resurrected a trunk story, spruced it up, and sold it. Often times, that’s because the story has a good premise, but I might not have had the chops to make the most out of it ten years ago. Now, with more experience, I can take some of these flawed pieces and polish them into something sellable.

There you have it. The fates of all my rejected stories. I’ll admit, I’m somewhat surprised at how it all shook out. The fact that the bulk of my rejections come from stories I eventually sell is, to be honest, pretty encouraging, and further proof that selling a story is about putting the right piece in front of the right editor at the right time.

Thoughts on all my no’s and not for us’s? Tell me about it in the comments.

2025: A Short Fiction Rearview Review

Posted on January 6, 2026 by Aeryn Rudel

Welp, 2025 is over, and it’s time to tally up my submissions, rejections, and acceptances and see how I did. I set some lofty goals for the year, and though I fell short of more than one of them, it wasn’t a terrible year, and in fact, in at least one way, it was one of my best years. Lets get into it.

Short Story Submissions

Here are the basic numbers for my short story submissions in 2025.

- Submissions: 122

- Acceptances: 10

- Rejections: 86

- Pending: 20

- No Response/Withdrawn: 6

- Publications: 8

So, 122 submissions is my record for a single year. I’d hoped to get closer to 150, which would have given me 1,000 submissions total since I started tracking them, but that’s gonna have to wait until the end of Q1 this year. Ten acceptances is solid, and once you factor in pending stories, no responses, and withdrawals, I’m sitting at just over a 10% acceptance rate. Not too bad. That number could even go up if some of the pending subs I sent in 2025 come back as acceptances. (Duotrope counts them for the year a sub was sent not when it was accepted.)

The 86 rejections feels a little light for the number of submissions I sent, honestly. The last time I hit 120 subs, I had over 100 rejections (more acceptances, too). I think some of that has to do with the fact that markets are taking longer to respond to submissions, likely due to an increase in the number of submitters, and some of that likely has to do with an increase in the number of AI submissions.

I also got A LOT of close-but-no-cigar and final-round rejections this year. I haven’t yet confirmed, but it feels like more than any other year. Lots of heartbreakers from pro markets, and it feels like I could have easily had another five or so acceptances if I’d had a little better luck/timing, but, you know, c’est la vie.

Publications

Despite getting ten acceptances, I only managed eight short fiction publications in 2025, and a few of those were from sales I made in 2024. Some of this has to do with pro markets having a longer lead times for publications. For example, the stories I sold to Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and Abyss & Apex were sent in 2024, accepted in 2025, and will publish in 2026.

Anyway, here are some of my 2025 publications that you can read for free online. (The others are behind a paywall.)

- “Care and Fiending” published by Factor Four Magazine

- “Coin Flip” published by Flash Point SF

- “The Other Side of Empty” published by Dream, Theory Media

- “Thicker Than Water” published by Radon Journal

- “What Hope’s Worth” published by MetaStellar

2025 Goals

As I said at the beginning of the post, I set some lofty goals for 2025 for short fiction. I met some of them, and well, others, not so much. I was tracking them in a bingo format (another goals I failed to meet), which I updated for this post.

Damn! Just missed the O!

As you can see , I did okay with submissions, production, and, of course, rejection goals. I struggled with sales goals. Still, there’s more green than white, so not too terrible. I might do something similar to this for 2026, but I’ll likely tone down the new story and sales goals just a tad. 🙂

And that’s my 2025 short fiction review. How was year in the submission trenches? Tell me about it in the comments.

Ten Years of Rejectomancy – ALL the Numbers

Posted on December 16, 2025 by Aeryn Rudel

So, this is truly the final post in my Ten Years of Rejectomancy series. As promised, I’m gonna give you ALL the numbers for each year and then a total of subs, rejections, and acceptances for the entire decade (plus the years before and this year). It’s been a blast to look back on the highs and lows of ten-plus years in the submission trenches, and I hope the journey has been inspiring, validating, and make a tad reassuring to those of you new to the submission grind. It’s tough, brutal at times, but if you keep at it, the acceptances do start piling up.

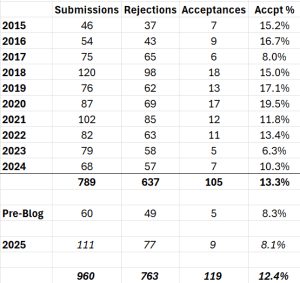

Okay, here’s the numbers for fourteen years of submissions. 🙂

So, in the ten official blog years, I managed 789 submissions and 105 acceptances. Not too bad, and good enough for 13.3% acceptance rate. I was over 15%, but 2023 and 2024 brought my career average down, and it looks like 2025 isn’t going to help much in that department either. Still, averaging ten acceptances per year is pretty solid, I think. You can see the pre-blog years and 2025 year-to-date (which may improve or worsen as I hear back on pending submissions), as well as an overall total for the 14 years I’ve been submitting short stories. I’m closing in on 1,000 submissions and 800 rejections, which are big milestones I should be celebrating in the first half of 2026.

I’d very much like to get back to double digit acceptances per year and push that acceptance percentage up to around 15% again. Things have gotten markedly tougher out there for a number of reasons. An inundation of AI subs at certain markets has increased wait times on submissions for one, and, sadly, there are just fewer speculative markets to submit to these days. I’m not complaining, mind you. You have to roll with the punches in this biz, but it is a noticeable downturn over the last couple of years. I guess it could simply be that I’m writing more garbage than I used to, but the number of final-round rejections I’ve been getting has actually increased, so as much as I’d like to believe I’m just getting worse in the ol’ writing department, that’s probably not true. 🙂

And there you have it, the entirety of my submission career and all ten years of the blog laid out in plain numbers. How’s your 2025 shaping up submissions-wise? I’d love to hear about it in the comments.

Finally, if you’ve missed any of my Ten Years of Rejectomancy posts and want to catch up, here are the links to all the others in the series.

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: The Pre-Blog Years

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year One – To Pro or Not to Pro

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Two- Maybe I’m Good at This?

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Three – Maybe I’m NOT Good at This?

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Four – Back On Track!

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Five – Consistency is Key

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Six – Best Year EVAR!

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Seven – The Whiplash Effect

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Eight – Solid and Serviceable

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Nine – A Question of Querying

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Ten – A Decade of Denial

Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Ten – A Decade of Denial

Posted on December 8, 2025 by Aeryn Rudel

Welp, here we are. Ten years of Rejectomancy. It’s been a long and bumpy road, and year ten certainly had its ups and downs, but it feels good to say I’ve been doing this for a decade, and I have no plans to stop. Our final year in this series is 2024, which was a definite improvement over 2023, though still short of satisfactory if I’m being honest. Things are getting tougher our there for a lot of reasons, but you gotta keep going, keep writing, and keep submitting.

Let’s have a look at Rejectomancy Year Ten.

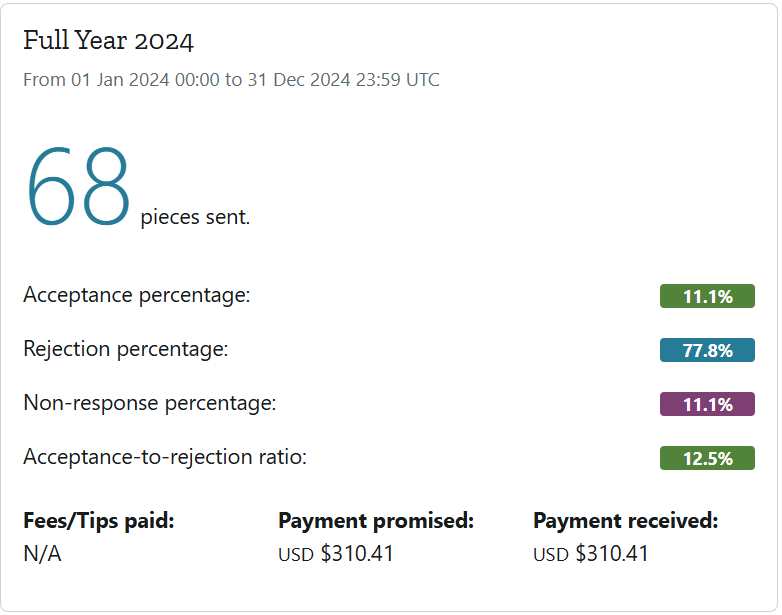

Total stats for 2024.

Like I said, an improvement over 2023, but I wasn’t exactly setting the literary world alight with my submission efforts last year. Still, seeing that acceptance percentage crest 10% again certainly makes me feel a bit better. There are no queries in here (I learned my lesson there), and these are all short story subs or direct novel submissions to small publishers, which are close enough to submissions to count in my humble opinion. Sixty-eight subs is decent, though my goal is always to send at least a hundred (I did manage that in 2025, btw). If I’d been a tad more industrious, I might have hit double-digit acceptances, but what are you gonna do. I’d call this a decent enough rebound from a fairly disastrous 2023.

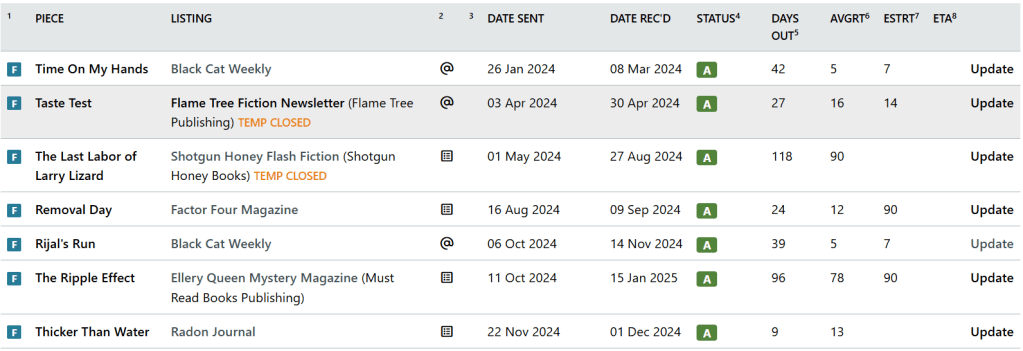

Here are my acceptances for 2024.

Seven acceptances in 2024, and most of them are to markets I’d sold to previously. The new market and one of my biggest short story sales to date is the sale to Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. That’s a big one, and I’m looking forward to it coming out in the 2026 March/April issue of EQMM. Another thing you might notice in my sales here are that four of the seven are either crime fiction or crime/sci-fi. I’ve often thought that I might have better luck selling to straight crime/mystery markets, and I have fairly convincing sample size. I’m not ready to make the switch yet, but it’s something I think about.

And that’s Rejectomancy Year Ten, which brings us to a close (almost) in this blog series. It’s been fun looking back over the years and digging in to the highs and lows of my story submission career. I do plan on one more blog post to give you all the numbers for the entire ten years–subs, rejections, acceptances, etc.–so look for that in the coming weeks.

If you’ve missed any of my Ten Years of Rejectomancy posts and want to catch up, here are the links to the others in the series.

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: The Pre-Blog Years

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year One – To Pro or Not to Pro

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Two- Maybe I’m Good at This?

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Three – Maybe I’m NOT Good at This?

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Four – Back On Track!

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Five – Consistency is Key

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Six – Best Year EVAR!

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Seven – The Whiplash Effect

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Eight – Solid and Serviceable

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Nine – A Question of Querying

Thoughts or opinions about Rejectomancy Year Ten? Tell me about it in the comments.

Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Nine – A Question of Querying

Posted on November 24, 2025 by Aeryn Rudel

Peaks and valleys. That’s the best way to describe the submission experience and my own meandering path as a writer. I’ve had some exceptional years where it felt like every story I submitted had a legit shot at publication, and then I’ve had years like 2023, where I thought, why the hell am I doing this again? Still, appearances can be deceiving, and what looks like one of my worst submission years ever is maybe a little more nuanced than that.

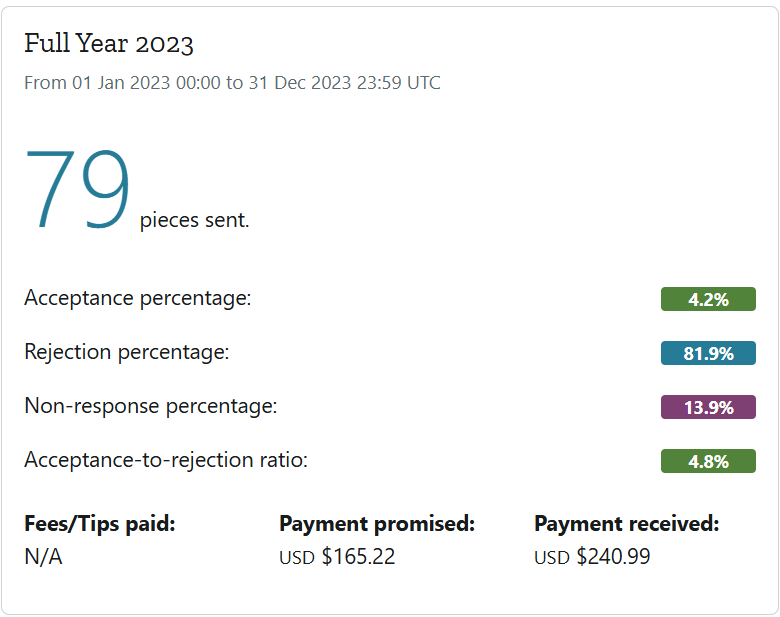

Let’s have a look at Rejectomancy Year Nine.

Total stats for 2023.

Oof, right? A paltry 4.2% acceptance rate is, well, not good. Now, I don’t shy away from owning my failures and terrible numbers, but this one time, I want to offer up an explanation for this massive drop in acceptance percentage. You see, in 2023, I started querying a novel, and I track my queries on another website called QueryTracker. Then I learned that Duotrope also lists agents, and I thought, hey, I should track my queries there, too. Obviously, I didn’t think that through, and well, this is the result.

So, of the 79 submissions I sent in 2023, 41 of them were actually queries for my novel Second Dawn. That means I only sent 38 short story submissions. So, with that number and the 5 acceptances I managed, my actual short story acceptance rate is 13%, which is more in line with my usual numbers. Still, it was my dumb ass that decided to track queries in the same place I track short stories, so I have to wear that 4.2% to some extent. 🙂

Here are my acceptances for 2023.

Just five acceptances in 2023, but they were all good sales. I sold my second story to Radon Journal, my third to Factor Four, and I had acceptances from new-to-me markets, Black Cat Weekly and Thirteen. Not too bad, especially when view through the prism of 38 submissions rather than 79.

And that’s Rejectomancy Year Nine. We’re getting close to the end of this series, so keep an eye out for Rejectomancy Year Ten – A Decade of Dejection. 😉

If you’ve missed any of my Ten Years of Rejectomancy posts and want to catch up, here are the links to the others in the series.

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: The Pre-Blog Years

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year One – To Pro or Not to Pro

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Two- Maybe I’m Good at This?

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Three – Maybe I’m NOT Good at This?

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Four – Back On Track!

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Five – Consistency is Key

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Six – Best Year EVAR!

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Seven – The Whiplash Effect

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Eight – Solid and Serviceable

Thoughts or opinions about Rejectomancy Year Nine? Tell me about it in the comments.

The Daily NO – Halloween Special

Posted on October 31, 2025 by Aeryn Rudel

Today on The Daily NO, we’re celebrating Halloween by looking at all the rejections I’ve received on the spookiest day of the year. However, to my shock and surprise, in over 12 years and nearly 1,000 submissions, I have received exactly ONE rejection on October 31st. The only reason I can come up with for this bizarre anomaly is that I submit to a lot of horror markets, and, well, it makes sense that horror editors are not working on horror’s holiday. 🙂

Anyway, let’s take a look at my Halloween rejection.

Halloween Rejection

- Story: “Things That Grow”

- Length: Flash Fiction

- Genre: Horror

- Publisher: Cemetery Gates

- Publisher Tier: Pro

- Submitted: 8/27/20

- Rejected: 10/31/20

- Type: Personal rejection

Hey Aeryn,

As personal rejections go, this one is short and to the point. It’s almost like a form letter in its brevity, which is fine with me. It simply says they liked the story, but it didn’t make the cut. This was for an anthology called Campfire Macabre, so I’m sure spots were limited. There’s no feedback here, so it’s important not to read into a rejection like this. They could have passed on it for a dozen reasons. They might have accepted another story with a similar theme, they might have needed something longer or shorter to fill out the anthology, or, hell, they might have just liked another story a little better.

This rejection did tell me I had a good story on my hands. This was the fourth personal or close-but-no-cigar rejection “Things That Grow” received, and I sold it on its next submission to The Flame Tree Fiction Newsletter. The takeaway here is if your story is getting rejections like this, it’s probably not a matter of quality; it’s more about putting that story in front of the right editor.

Thoughts on this rejection? Tell me about it in the comments.

Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Eight – Solid and Serviceable

Posted on October 28, 2025 by Aeryn Rudel

Although 2021 wasn’t a terrible year for submissions, I definitely went into 2022 hoping to improve, and in some ways I did. Mostly, though, I kind of held course with a solid but not exceptional year. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it was definitely one of those years where I felt like I was just treading water in a lot of ways. (Spoiler alert: 2023 will show me the error of this thinking.)

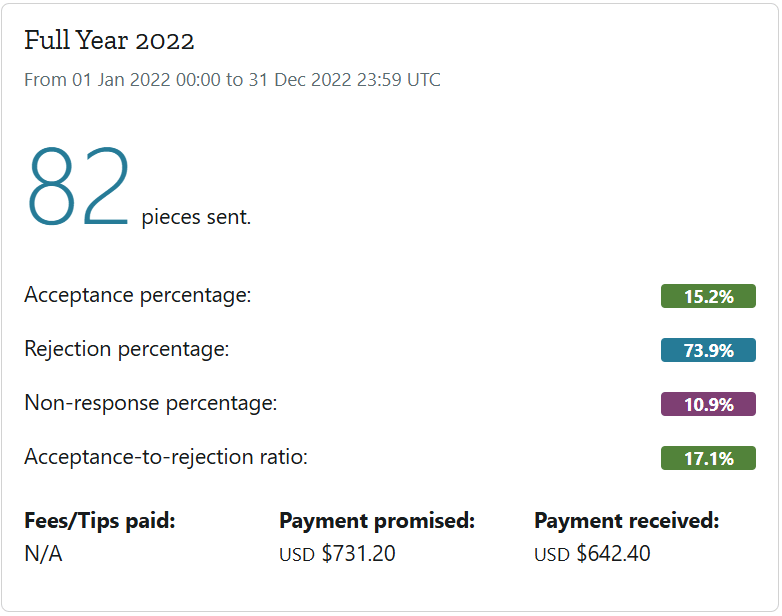

Okay, let’s have a look at Rejectomancy Year Eight.

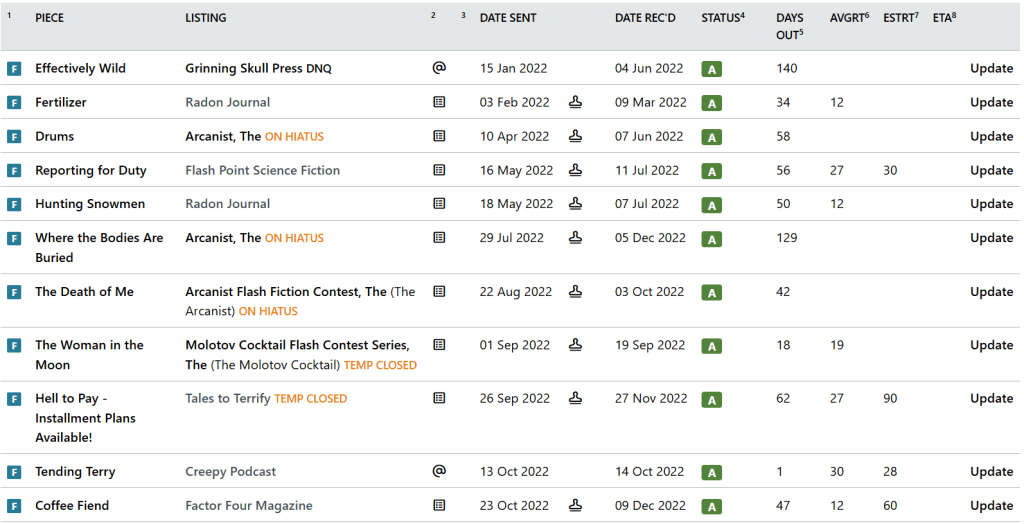

Total stats for 2022.

Although I didn’t hit the vaunted 100 submissions mark in 2022, I still sent out a respectable number of stories. Also, my acceptance percentage improved quite a bit over the year before, jumping from 9.6 to 15.2. That ain’t bad. I was also paid more than double for the stories I sold in 2022 over those I sold in 2021. The money I make from shorts is not anything I rely on, but it’s always good to get paid. Looking at it now, three years later, I likely misjudged this year. It’s better than I gave it credit for.

Here are my acceptances for 2022.

I sold 11 stories in 2022, though one of the stories was actually a novella, Effectively Wild, that I sold to Grinning Skull Press. Most of my other sales were to pro or semi-pro-paying markets, though there’s a bittersweet sale in here. The story “Where the Bodies are Buried” is the last story The Arcanist published before going on indefinite hiatus. Fun fact, my story “Cowtown” was the first story they published back in 2017, so I bookended the publishing run of that market. God, I miss those folks.

The other positive here is that four of the stories I sold where new-to-me markets, which is always great, and one of them, Radon Journal, has become one of my absolute favorite publishers on the planet. I’ve since sold them three more stories, and I’m quite active on the Discord server. I also managed two sales to Factor Four Magazine, another market that has become one of my go-to’s for flash fiction.

And that’s Rejectomancy Year Eight. Not bad, not great, but serviceable. Again, spoiler alert, in 2023, I will definitely look back on this “mediocre” year and realize how good I actually had it. 🙂

If you’ve missed any of my Ten Years of Rejectomancy posts and want to catch up, here are the links to the others in the series.

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: The Pre-Blog Years

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year One – To Pro or Not to Pro

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Two- Maybe I’m Good at This?

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Three – Maybe I’m NOT Good at This?

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Four – Back On Track!

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Five – Consistency is Key

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Six – Best Year EVAR!

- Ten Years of Rejectomancy: Year Seven – The Whiplash Effect

Thoughts or opinions about Rejectomancy Year Eight? Tell me about it in the comments.

Hitting the Ton: 100 Submissions

Posted on October 22, 2025 by Aeryn Rudel

I’m a car and motorcycle enthusiast, and one of my favorite bits of (now outdated) slang is “hitting the ton”, which means going over 100 miles per hour (usually on a motorcycle). For me, there’s a literary version of hitting the ton, too, and that’s getting 100 or more submission in a calendar year, something I achieved for the third time in my career a few days ago. So, I thought I’d do a little post about it and talk about what it takes to hit the ton. 🙂

First, lets look at the stats.

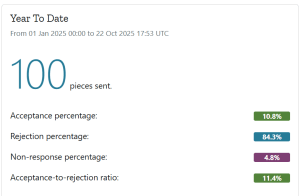

So, as you can see from the screenshot I just took from Duotrope, I’m still sitting at exactly 100 submissions, and here’s how that 100 subs breaks down.

- Submissions: 100 (obvs)

- Acceptances: 8

- Rejections: 67

- Pending: 21

- Withdrawn: 2

- Never Responded: 2

It’s been a tough year, and my acceptance percentage, though not terrible at just under 11%, is not where I’d like it to be. Lots of close-but-no-cigar rejections. Still, it could be worse, and the bright spot is that I’ve managed to break through with some prominent markets, including Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and Abyss & Apex. I also still have 21 subs pending, and there might be another pro sale or two in the mix. If I can end the year with around a dozen acceptances, all of them paid, and half of them at pro markets, I’d be satisfied.

Now let’s talk about what it takes to hit 100 subs (or more) in a year.

- New Material: It goes without saying that to send a lot of submissions you need a lot of stories to submit. One of the goals I set for myself this year was to write a new story every week. I even maintained that pace for three or four months before I burned out. Still, the sixteen new stories I wrote in those first few months, plus another dozen I’ve written since has given me plenty of grist for the mill. There’s also some resuscitated trunk stories in my 100 subs, two of which I even sold.

- Consistency: To send 100 submissions, you need to send roughly 8 submission per month, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but even with a bunch of new stories to work with, you can run out of markets fast. I’m constantly doing research to find new markets and keeping my eyes peeled for markets opening to submissions. I’ve been shooting for 10 submissions per month, and, for the most part, I’ve hit that. I set a monthly goal, and try to plan my subs around markets that are opening to submissions. For example, I’m ever watchful for Uncanny, Apex, Strange Horizons, and a few others to open up so I can fire off a submission before they close again.

- Perseverance: If you send a lot of submissions, you’re gonna get a lot of rejections. Hell, even if you somehow manage an otherworldly acceptance percentage of 20%, you’re still looking at EIGHTY rejections from 100 submissions. That’s a lot, and let me tell ya, those rejections tend to come in bunches. There’s a 28-straight-rejection streak in my current 100 subs, and that kind of thing can wear on you, even if you’re used to the slings and arrows of the process. So take those rejections in stride and keep sending those stories out the door.

And that’s how I got to 100 submissions this year. My record is 120, and with two months and change to go, I might be able to beat that. Another, loftier goal I’d like to hit is 1,000 submission since I started tracking them on Duotrope back in 2012. I need 55 for that, though, so unless I find some boundless reservoir of writing energy between now and the new year, that’s probably unlikely.

How’re your submission going? Closing in on any personal goals? Tell me about it in the comments.