September 2016 Submission Statement

September was a solid month, and my progress with short story submissions was much less sloth-like than previous months. It’s a mixed bag this time, with rejections, acceptances, and some noteworthy publications.

September Report Card

- Submissions Sent: 7

- Rejections: 5*

- Acceptances: 1

- Other: 0

- Publications: 2

*Three (3) of these rejections were for submissions sent in September.

Rejections

Here we go. This is what Rejectomancy is all about! Five rejections this month; let’s have a look.

Rejection 1: 9/3/16

Thank you for your submission to XXX.

We regret that we are unable to publish “XXX” We are grateful for the opportunity to consider it, and we wish you the best of luck in placing it elsewhere.

A common form rejection from one of the bigger horror markets. Nothing much to see here, really, and I’ve received this exact rejection numerous times. This will be a running theme for September, by the way.

Rejection 2: 9/3/16

Thank you for your interest in XXX, unfortunately, your story does not fit our needs at this time.

As this is a brand new publication with no real backdrop of study, you should not take this rejection personally. Please submit again in the future, however, no sooner than 20 days from the date of this notice.

The 3rd was a multiple-rejection day, and this one is from a brand new market. It’s a pretty standard form rejection, but I like the note they tacked on at the end. I don’t put a lot of stock in this canned niceties you often see in rejection letters, but this is always good advice. Rejections are NOT personal.

There’s one other thing about this rejection that’s a bit different. They ask you not to resubmit for a period of 20 days. It’s not uncommon for publishers to do this, though I usually see it in their submission guidelines. I think it’s a good idea for a publisher to remind writers of this particular rule in a rejection, since it’s likely you haven’t looked at the publisher’s guidelines in quite some time, and the rejection will be fresh in your mind.

Rejection 3: 9/12/16

Thank you for the opportunity to read “XXX.” Unfortunately, your story isn’t quite what we’re looking for right now.

In the past, we’ve provided detailed feedback on our rejections, but I’m afraid that due to time considerations, we’re no longer able to offer that service. I appreciate your interest in XXX and hope that you’ll keep us in mind in the future.

Remember that theme I talked about in rejection number one? So, I finished a new story this month, and, as I usually do, I’m sending it to all the top-tier markets that accept horror. These are all exceedingly tough markets to crack, and I’ve received lots of form rejections, like this one, from all of them. Anyway, this is another standard form rejection. Moving on.

Rejection 4: 9/14/16

Many thanks for sending “XXX”, but I’m sorry to say that it isn’t right for XXX. I wish you luck placing it elsewhere, and hope that you’ll send me something new soon.

Another standard form rejection from a top-tier horror market for the same story as the previous rejection. What’s great about these markets is they’re really fast, usually taking no more than a couple of days to send a rejection. So, I can usually hit three or four of them in the same week.

Rejection 5: 9/15/16

We have read your submission and will have to pass, as it unfortunately does not meet our needs at this time.

Remember when I said these top-tier markets are quick? This one is by far the quickest, and this rejection came within an hour and a half. That’s not even my record for this publisher. I once received a rejection in 46 minutes. I honestly don’t know how they do it, but I appreciate the lightning-fast response. Another standard form rejection, likely recognizable to anyone who regularly submits to the pro horror markets.

Acceptances

One acceptance this month, though it comes with a catch (see below).

Acceptance 1: 9/10/16

Normally, on the blog, I’ll share just about everything with you when it comes to ejections and acceptances, but this is one of those times where I can’t. The acceptance letter for this month contains some information I’m not at liberty to divulge, and there’s really no easy way to excise that info from the letter. I’ll just say that it’s an acceptance from a market that’s published me once before, and it’s a story I’m really excited about. I’ll post more info when I can.

Publications

My two publications this month are a little out of the ordinary in that they’re both audio publications.

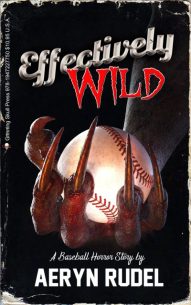

Publication 1: 9/23/16

Man, I was excited for this one. I sold my vampire/baseball story “Night Games” to Pseudopod way back in December of 2015. As you can imagine, a market like Pseudopod needs a bit more time to prepare a story for publication, what with securing voice work, recording, editing, and so forth. In addition, the editors thought it would be fitting to publish the story at the end of the 2016 baseball season, and I wholeheartedly agree.

The narrator, Rish Outfield, did a fantastic job, and I couldn’t be more pleased with the way the story turned out. Normally, I wouldn’t harangue you to go out and read/listen to one of my stories, but in this case, I’m gonna. Why? Well, “Night Games” is my favorite of the stories I’ve written thus far, and I think it’s very indicative of my writing style (that’ll be good or bad depending on your point of view and tastes). And, seriously, the narration is just awesome. It’s worth the price of admission all by itself (the story is free to listen to, by the way).

Publication 2: 9/27/16

Flashpoint – Privateer Press/Audible

So the second publication is the audio version of my Iron Kingdoms novel Acts of War: Flashpoint. Again, the narration, this time by Noah Levine, is top-notch, and it was really cool to hear all the characters in the book come to life. I was really happy with the way this turned out, and I’m grateful to Noah and Audible for doing such a bang-up job.

Anyway, if you’d like to listen to Flashpoint, click the pretty picture below.

And that was my September. How was yours?

7 Top-Tier Horror Markets: My New Story Gauntlet

Once I’ve finished a new story and it’s ready for submission, I have a short list of top-tier spec-fic markets that it goes to first. I have dubbed this list “The Gauntlet,” and they are some of the toughest but most prestigious publications I know of that accept horror. They also work very fast, and I often get a response to my submission within a few days or even a few hours.

Here’s my list, presented in no particular order:

- Clarkesworld Magazine

- The Dark Magazine

- Nightmare Magazine

- Black Static

- Pseudopod

- Apex Magazine

- DarkFuse Magazine

My current record with these publications is one original acceptance (DarkFuse Magazine), one reprint acceptance (Pseudopod), one further consideration letter (Apex Magazine), and a whole bunch of rejections (every last one of them). The order in which I submit a story (or if I submit a story at all) is due in large part to when these markets are open to submissions, the length of the story, and which market is best suited for the piece. Like I said, these are some of the toughest publications to crack in the spec-fic market, and most of them have acceptance rates well under one percent according to Duotrope. And, let’s face it, that acceptance rate is probably a lot smaller because rejections are more likely to go unreported than acceptances.

One quick note about response times. I mentioned earlier that these publications work fast, and they do for an initial response. That’s usually a rejection, but in my experience, these markets will send you a note if they’re considering your story for publication. After that, the wait can be much longer, months even, before you hear from them again. That said, I’m thrilled to just be considered by these publications, so that second wait, when it happens, isn’t too bad. Some of these markets do accept sim-subs, by the way.

So, why submit to these markets first? Here are four good reasons.

1) Reach. From what I’ve been able to gather through a bit of internet research, most of these markets have readerships in the thousands or even tens of thousands. So if you can manage to get a story accepted by one of them, that story is going to be read by a lot of people interested in the type of fiction you write. That’s the kind of thing that helps you build a brand and can maybe affect the sales of something like that novel you’re thinking about self-publishing some day

2) Group memberships. Stories accepted by these markets often count toward membership in professional writing organizations like the HWA (Horror Writers Association) and the SFWA (Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America). If you want to be a member in one of these groups and get access to the benefits that entails, you have to publish at qualifying markets. All the markets in my list qualify for one or the other or both.

3) Awards. If you’re a spec-fic writer who dreams of winning awards like the Hugo Award or the Bram Stoker Award, then publishing at one or more of these markets (and others like them) is a good step toward the fame and glory you seek. Stories nominated for both awards and probably a few others are often drawn from the pages of some of the publications on my list.

4) Pro rates. Simply put, these markets pay the most. Nearly all of them pay the pro rate of .06/word, and some pay a lot more. For me, money is at most a tertiary consideration, but getting a chunk of cash for a story is still awfully damn nice.

Some of you might be wondering why I haven’t included one or more [super huge famous spec-fic] markets on my list, and the reasons are pretty straightforward. Factors that disqualify a market from my gauntlet include but are not limited to:

- Longer wait. I don’t usually submit to markets that take longer than 30 days to respond in my first go-around unless the story is just a perfect fit. I’ll invariably start hitting these markets once the story has run the gauntlet, so to speak.

- Bad fit. I write horror in a fairly specific style, and there are magazines that just don’t publish the kind of horror I write. For example, I rarely write anything that could be considered weird fiction, a popular fantasy/horror subgenre.

- Content restrictions. A few top-tier publications have a strict PG-13 content restrictions, and while there’s nothing wrong with that, I just have trouble writing without an R-rating. I have a strict rule that the word “fuck” must appear at least twice in every one of my stories (a personal failing, I know).

- Ignorance. Yep, finally, there are probably lots of great markets I just don’t know much or anything about. Please enlighten me in the comments if you know of one that should be on my list.

So, there’s my gauntlet run (so far) and the reasons new stories typically go to these markets first. Got a gauntlet run of your own? Maybe for another genre? I’d love to hear about it in the comments.

August 2016 Submission Statement

Well, August was certainly better than July, where I did pretty much nothin’ in terms of submissions. I managed to get a few stories out last month, and I even snagged an acceptance and a publication.

August Report Card

- Submissions Sent: 3

- Rejections: 1

- Acceptances: 1

- Other: 0

- Publications: 1

Rejections

Here’s the lone August rejection.

Rejection 1: 8/14/16

Thank you for submitting work to our Flash Icon contest. There were some incredibly high-quality entries submitted this time around.

Unfortunately, “XXX” didn’t make it into our Top 10. However, we encourage contest participants to submit these stories for consideration in our regular issues (free to submit) if you’d like to do so.

Thanks so much for your participation. We couldn’t do these contests without you.

This is another entry into one of The Molotov Cocktail’s flash fiction contest. This one was called Flash Icon and challenged writers to include an iconic person, place, or thing. I went kind of far afield on this one and chose an obscure monster from Greek mythology as my “iconic” thing. I don’t know why I thought a hecatonchire, even a named one, would be even remotely iconic, but there you go. I’m not saying that’s why this story didn’t place, but I’m guessing it didn’t help.

Acceptances

One acceptance, and, yep, it’s from the same place as the one rejection for the month

Acceptance 1: 8/14/16

Once again you’ve dazzled us with some strange and compelling flash fiction. “The Father of Terror” has won 2nd place in Flash Icon. Dead cats and slumbering Egyptian demons are right up our alley.

By now, you know the drill. This piece will be included in the mega-issue by mid-week and it will be in the Prize Winners Anthology due out this fall.

A very nice acceptance letter, and I always love working with the folks over at The Molotov Cocktail. My story “The Father of Terror” took second place in the Flash Icon contest. My iconic thing in this one was the Sphinx, and I’m not saying my choice of an ancient, immediately recognizable structure was the key to my story placing, but it’s a damn sight better than a Greek monster no one has heard of.

Anyway, always nice to get another one on the board, and the fact that it’s with one of my favorite publications is just icing on the cake.

Publications

Yep, it’s a three-for. The one publication is at, you guessed it, The Molotov Cocktail.

“The Father of Terror” was published in their Flash Icon mega-issue, which you can read right here. As usual, this contest collection is chocked full of great stories, and if you dig horror and flash fiction, it’s a must-read.

The other thing I’d like to call your attention to is not a publication but a flash fiction contest out at Red Sun Magazine. You might remember they published my story “Paper Cut,” and they’ve been kind enough to base this contest around my novel Flashpoint and to offer the book as part of the prize packages. Anyway, if you write flash fiction, head over to Red Sun for the official rules.

That was my August. Tell me about yours.

Rejectomancy Exclusive – The Barghest by Orrin Grey

As I mentioned in this post, my very talented writer friend Orrin Grey is re-releasing his first collection of short stories, Never Bet the Devil & Other Warnings through Strix publishing. You can check out the Kickstarter campaign right here. Orrin is a horror writer, and a damn good one, and he and Strix Publishing have given me permission to post one of the stories in the collection here. So, check out the “The Barghest” below for a taste of what you’ll get in the premium re-release of Never Bet the Devil & Other Warnings. If you’re a fan of weird fiction and horror in general, this is one you don’t want to miss.

The Barghest

By Orrin Grey

I was standing by the side entrance when they brought in the bones. Would you believe me if I said that as soon as I saw them I knew they weren’t human? Or any other indigenous animal? I wouldn’t blame you if you didn’t. It’s a difficult thing to credit.

It wasn’t any training that told me, or my experience at the museum. I didn’t see the bones long enough for that, just a glimpse of the brown skeleton–the wrong-size skull, the wrong-way legs–and some primal part of my brain said “monster.”

I threw away the butt of my cigarette and followed the men who were carrying the stretcher with the skeleton on it. I wasn’t surprised when I saw that they were carrying it to your part of the lab.

I remembered you on the phone, arguing with Kelso over a skeleton that was found out on the moors somewhere. You wanted it, you said. The museum had paid for the dig, and you were the senior paleontologist on staff so it belonged to you.

You were waiting when they laid the stretcher on the table. That’s when I got my first good look at it. It was the size of a big man, but it definitely wasn’t a human skeleton. Looking at the bones, I was hard put to say if it was a biped or a quadruped. I imagined that it moved like a bear, or like a great ape. Its hands were too big for a human and terminated in hooked talons, but they had clear opposable thumbs.

The skull was simultaneously apelike and doglike, a toothy muzzle like a baboon or a mandrill. I remember making some offhand comment about Lovecraft’s ghouls, but you were unfamiliar with Lovecraft. You never cared for anything you deemed “disposable culture.”

As the investigation into the remains went on I bought a copy of Tales of H.P. Lovecraft edited by Joyce Carol Oates, whose name I thought might lend it some credibility in your eyes, and gave it to you with the page containing “Pickman’s Model” tagged. I’ll bet it’s still on the shelf in your office, with the tag still on it. I’ll bet you never even picked it up.

If you had read it, though, you would have understood why I brought it up; you would have known what it was about the bones that left me at once intrigued and uncomfortable. How human they looked, and how inhuman. Not like the bones of some Neanderthal man, some earlier species of humanity, but instead like something that took an alternate evolutionary path, something that should have been human but became something else instead.

Those sorts of thoughts didn’t interest you, though. I know that. You were always dismissive of what you called my “supernatural thinking.” You always regarded the museum as beneath you, and me as beneath the museum. You treated me with a grudging tolerance, and never admitted that the reason we worked together was because none of the other interns would work with you.

“What is it?” I asked you that night, because for all your coolness you liked it when I asked you questions, and because I really did want to know what you thought. I was curious if you had some explanation that would take all the parts and somehow make of them something other than a monster.

“Something new,” you said, and that was all. It was less than encouraging.

Of course, it wasn’t something new, was it? It was as old as the dirt in which it was found, as old as men telling campfire stories. We learned that, you and I, but you learned it first.

#

I remember how carefully you cleaned the bones. The peat in which they were found had preserved them, like a fossil without the stone. They were perfect; no flesh left for us to macerate, just those ossified brown bones. I remember watching you work over them with your little brush, your magnifying glass, carefully turning over and examining each and every tiny piece.

I wasn’t allowed to do any of the real work, wasn’t to handle the skeleton. When I was in the lab, I stared at the skull.

As with most carnivore skeletons, the skull seemed too big for the rest of the bones. It dominated the table, drew the eye. Those teeth that seemed too big for the mouth they filled, those gaping sockets. If I looked at it one way it was pure animal, like a wolf or tiger, if I looked at it another it was disturbingly human.

I’ve spent a lot of the time since then wondering how it happened. You were so careful. Was it your eagerness that was your undoing, or did something else render you suddenly clumsy? Were the teeth simply sharper than you imagined they would be, after remaining buried for so long?

You know how, sometimes, when you walk into a room, you can tell that something has changed before your mind has processed what it is? When I walked back into the lab that night, I knew that something was wrong before I took in any of the details. From where I was standing in the doorway, I could see the skeleton on the lighted table, and my eyes naturally traveled to where the skull would normally have rested, only to find a blank white space where it should have been.

Only then did I notice that you weren’t there. I walked to the head of the table. The skull was on the floor, teeth and pieces of jaw scattered across the tile. And mixed in among them were fat red drops of blood.

I went to the break room then, but you weren’t there, just more drops of blood spattered on the back of a chair and the surface of one of the round Formica tabletops. The first aid kit on the wall hung open, and pills in individual packets lay scattered across the counter and the floor.

Why did you go to the ladies’ room, I wonder? Was it shame, fear of appearing mortal and fallible in front of the help? Or did you know, even then, that something was wrong, more wrong than the gouge in your palm or the blood you were losing from it?

I knocked on the door, and you knew it was me. “I’m fine,” you said, without my even needing to inquire. “It’s just a scratch. Go clean up the lab, and be careful.”

At the time I thought nothing of that “be careful.” I assumed it was concern over the integrity of the bones, displaced anger at the damage to the skull. But since then I’ve wondered. Did you know, even then? Was your concern not for the bones at all, but for me? It doesn’t seem like you, but then adversity sometimes brings out the best in people.

I have a lot of questions that I know will never be answered, but the one that troubles me the most is how soon you knew. When did you first realize what was happening, and how long did it take that realization to become knowledge, to become acceptance?

#

By the time you came out of the restroom I had already replaced the skull on the table and mopped up all the blood, both in the lab and the break room. If you were there I know you would have rolled your eyes at me, but as I put the skull back onto the table the black sockets looked darker and deeper than they should have, and I got the feeling that something was staring out of them at me.

I knew you’d been lying about it just being a scratch, I’d cleaned up too much blood for that, but it wasn’t until you came out of the restroom that I realized how bad it must have been. Your face was pale, the color bleached from it, like a person about a minute away from going into shock. Your eyes looked red, as if you’d been crying, and your right hand was swathed in most of the gauze and bandages from the first aid kit.

When you came into the lab you held your injured hand up to your chest like a cat with a hurt paw, and you put your other hand out to a table to steady yourself.

“That looks like it might need stitches,” I said, though of course I couldn’t see the wound itself. “You should probably let me take you to the emergency room.”

You nodded tightly but didn’t let me take you to the hospital until you’d examined the skeleton and verified for yourself that the damage wasn’t extensive enough to compromise the find. I noticed even then, though, that you were careful not to touch it.

#

The doctor at the ER put eleven stitches in the palm of your hand, and just like that I became necessary to you. With one hand out of commission, you couldn’t do the fine work needed to examine the skeleton, and so I became your hands on the job.

Did you ever stop to wonder why I worked with you when no one else would? Why I was willing to pull down the same preposterous hours that you insisted on? Did you think that I was attracted to you? Or did you just think that I believed you were the genius that you believed yourself to be, and that I wanted to ride on your coattails?

Maybe you didn’t think about it at all. That would be more like you.

Someone else might have noticed something different about you immediately, might have caught on sooner, for good or ill. Had I watched TV or read the papers I might have heard about the girl who was mauled to death in a park near your house that week, might have said something to you that would have forced a confrontation, elicited some response in you that I could have interpreted. But by the time I came home from the museum I was exhausted and all I wanted to do was to curl up with my ghost stories, which you regarded so scornfully, and then sleep.

Maybe it wouldn’t have mattered what I noticed, what I said. Maybe you still didn’t know yourself. I’ve not yet determined how aware you are when it happens, how much of you is left.

You always said that the surest road to combat superstition is study, but no matter how much we examined the bones I was never able to shake the sensation that they were not the remains of anything wholesome or natural, not even the bones of some mutation or aberration, some lusus naturae. You, of course, were no help.

I bought a book of folktales from the British Isles and took to reading it before I went to bed. I read about Black Annis, a cannibal witch who lived in a cave under an oak and ate children. She hung their skins in the branches to dry, and then wore them tied around her waist. I read about Black Shuck, a dog the size of a horse with eyes like saucers, and the more recent “shug monkey,” which reminded me more than a little of the thing on our table, with its mix of primate and canine features. I read about the shapeshifting Barghest, which may have inspired Dracula’s transformation into a monstrous wolf.

If I ever told anyone but you what I’ve seen since then, what I’ve learned, they’d send me to a psychologist, and that psychologist would undoubtedly blame my “hallucinations” on those stories. They’d say that I’d been priming myself, and that when events occurred that I couldn’t deal with, I used those myths to give context to a truth that I didn’t want to admit. But, as you always said, psychology is a soft science, and what happened to you, to us, is anything but soft.

Looking back now, everything seems so inevitable. Maybe if you’d been allowed to keep the skeleton, things would have gone differently. Maybe the charade could have been maintained a little longer, but I think it was doomed to come down, sooner or later.

I remember when, just two weeks after the night you cut your hand, Ms. Trevayne asked you to come into her office. She didn’t draw the blinds, and I knew just by watching what she was saying to you. You stood in front of her desk, your wounded hand drawn into a fist at your side, your other hand gesturing as you shouted at her.

When you stormed out of her office you called her a cunt, a word I’d never heard you use before, and told me that she was taking the skeleton away from you and giving it to Kelso, which I had already guessed. This would never have set well with you, even before, but you would have approached it disdainfully, with an “it’s their loss” attitude, as though you were too good to get upset. Your desperate rage took me by surprise, and when you walked back to the lab you forgot yourself and slapped both your hands palm down against the table. That’s when I knew. Knew that you weren’t hurt anymore, that your hand had healed completely even though the stitches weren’t due to be taken out for another week.

“She can’t do this to me,” you said, an under-the-breath growl I wasn’t intended to hear. “She can’t do this to me. Not yet.”

#

But of course she could, and when I walked into the lab that night and saw the table empty I knew she had.

You weren’t there, and I assumed that you’d already left in a huff. I almost just turned around and went home. How differently would things have gone then?

Instead, I decided to head across to the other side of the wing, to the lab that Kelso normally used. It’d be nice to say that some premonition prompted me, but I don’t think it did. I think I was just curious. I’d never seen you defeated, I was curious to see what someone else’s victory over you looked like.

As I rounded the corner I could see the light from Kelso’s lab flickering and swaying, like the illumination of some sideshow spookhouse. I think I ran to the door, then, but I don’t really remember. As vividly as I can recall everything else, the order of the next few seconds are jumbled in my memory. It’s as though everything I saw exploded into my mind at once, a kaleidoscope of snapshots.

The half-smashed light fixture that had come loose from the ceiling and was swinging back and forth, throwing its funhouse illumination on everything. The blood, shockingly red against the tile and the table and the wall. Kelso’s arm, in one corner, the rest of him crumpled behind the table. All of those things, though, were driven out of my mind when I saw the thing you had become.

It had taken only a glimpse of the bones for my primate brain to realize that they belonged to a monster, a teratism, something that should not exist. Seeing you like that took even less.

The thick black fur. The way you stood, crouched and bent, like a man who has been forced to crawl on all fours for years. The snout, like a wolf’s only crushed in, the teeth too large to fit in the mouth. The hands like Halloween monster gloves, only the claws making them seem real, reminding me of Black Annis and her iron talons.

You looked at me, I remember that. Your eyes weren’t big as saucers, but they were red and bright and amazingly clear and strangely human. I believe, to this day, that I saw recognition in them. That you saw me and knew me and chose to spare my life. Then you were gone out the window.

#

I didn’t call the police. I stumbled over to the wall, hit the fire alarm, and then collapsed to the floor beneath it. The sprinklers kicked on and I sat in the artificial rain, with my knees drawn up to my chest, and didn’t move until the authorities arrived.

The sprinklers probably destroyed the crime scene, but the police would never have been able to understand what had happened there anyway. I don’t even remember what I was asked, or what I told them, but I know that I didn’t mention what I really saw.

I remember being told that I was in shock. I remember someone wrapping a blanket around my shoulders as I was helped into an ambulance and driven to the hospital. It was only then, while I was sitting in the emergency room in my wet clothes, that I remembered the thing that I had seen but not noticed earlier.

The bones, of course. They hadn’t been on the table, and in one of your big, misshapen hands you had carried a canvas bag just big enough to contain them.

They let me out of the hospital eventually and took me back to my apartment. They told me to stay there, but I didn’t. I changed into dry clothes and then took a taxi to your place.

It wasn’t the first time I’d been to your house, of course. You’d sent me to pick things up for you from the museum before. I even knew where you kept your spare key stashed, though it didn’t turn out to matter because the back door was hanging open, the knob torn out of the wood.

I can’t say what made me walk through that door into the dark interior of your house. Maybe I was still in shock.

I didn’t turn on any lights. I walked through the kitchen, letting my eyes adjust to the darkness. There were smudges on the walls beside the staircase that looked like chocolate syrup in the dark, though I knew they weren’t. I followed them upstairs.

You were lying facedown on your bed. The blinds were drawn, but a wedge of streetlight came in through a gap in them. You were naked, your skin pale and human in the dim light, looking as smooth and new as the flesh of a baby. The bag of bones was on the floor beside the bed. I stood watching you for longer than I probably should have, measuring the rising and falling of your breath as you slept. Then I took the bag and walked back out.

#

I’ve not yet guessed why you wanted the bones so badly. Did you hope to extract from them the secret of a cure, some tincture of silver nitrate and wolfsbane? Or was it simply that you wanted to keep them close to you, your only connection to the thing you had become? Either way, it doesn’t matter anymore. I burned the bones in the incinerator in the basement of the museum before I made this recording. All but this one tooth.

Even if I hadn’t, though, it wouldn’t have made any difference. Cures are for movies, not real life. I don’t know what you are any more than I imagine you do, but I know it’s not something you get to come back from. Soon, though, you won’t have to be alone anymore. You’ll have something better than bones for company.

What does it feel like, when you change? I bet it isn’t like the movies, the gradual shifting and lengthening of bones, the sprouting of fur. I bet the beast just tears out of you, as though it’s been there all along and your skin is just a disguise that it’s been wearing. I’ll bet that’s what it’s like.

I don’t know if you’ll ever see this video. I don’t know how long it will take you to come for me, or even if what comes for me will be something that can properly be called “you.” But I know that you will come for me, sooner or later, and that when you do I’ll be here waiting for you, ready to meet you head on.

You see, I’ve torn my hand with this tooth, just as you did. I’m coming to meet you now, just as surely as you’re coming for me. I’m coming to join you in wherever you’ve gone, whatever you’ve become, and we’ll let nature–or whatever it is that governs things like us–take its course.

AUTHOR’S NOTES:

This one had its origins in, of all things, a terrible movie called Werewolf that I saw on an episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000. Maybe not the most auspicious of beginnings, but I thought the idea of someone becoming a werewolf because they were scratched with a fossilized tooth or bone from a werewolf was a setup that deserved some better treatment than a film starring Joe Estevez.

That was where it started, but once I was writing I realized that I didn’t want this to be a werewolf story exactly. At least, I didn’t want to use the word werewolf anywhere in the story. Giving something a name like that is an easy way to dismiss it. “Oh a werewolf, I know what that is,” so instead I decided to build the monster up using suggestion and allusion. I’d wanted to do something with some elements from British folklore like Black Annis and, of course, the Barghest, and I found that this was the perfect story for it. Throw in some more allusions to Lovecraft’s ghouls, and there you go.

Fightin’ Fiction: 5 Melee Myths

One of my many hobbies is HEMA, or historical European martial arts, wherein folks study various fighting manuals from the medieval and renaissance periods and attempt to recreate these martial disciplines as accurately as possible. Once you swing a sword the way it’s meant to be swung and then do a little historical research, you quickly find popular media presents combat with swords, axes, maces, and other crushy, stabby, pointy things . . . well, uh, incorrectly would the nicest way to put it.

So, from the author’s perspective, if you wanted to portray your melee combat more realistically, how would you go about doing it? Well, research is always the best answer, and it couldn’t hurt to at least watch some HEMA sparring to get an idea of what certain types of sword fighting probably looked like (or even take a few classes yourself). That said, I think the five “myths” I’m going to debunk below are a good place to start. At least, they’re things that jump out at me when I’m watching movies or TV that feature sword-fighting and such.

Let me preface this list by saying I have probably violated every one of these “rules” in my own writing for various reasons (“cuz its cool” being at the top of the list), so, please, don’t take this as me laying down the gospel. The idea here is not to remove the fun from fight scenes but to identify a few easy fixes if you wanted to present melee in a slightly more realistic fashion. If that’s not your thing, you’re not wrong by any means. There’re a lot of ways to write good action scenes in fiction, and ultra-realistic is not everyone’s cup of tea.

Okay, here we go.

1) Swords don’t go SCHWING! when drawn.

Go get a butter a knife, wrap it in the sleeve of your leather jacket, and then pull it free. What noise did it make? None, right? Yep, unless the sword is pulled from a metal scabbard, that cool SCHWING! sound you hear in every single movie doesn’t happen. Most scabbards are made of wood and leather, and even with a metal throat they don’t produce much noise at all. Swords also don’t sound like angry tuning forks, buzzing and hissing every time the hero flicks his wrist.

The fix: Easy; let your swords be silent, and let your hero’s deeds do the talking.

2) Back scabbards are impractical for big swords.

It’s a simple matter of physics, really. If you stick a big sword in a scabbard across your back, say a longsword with a 36-inch blade, your arm simply isn’t long enough to pull the sword up and out of the scabbard. You’ll get about halfway and then have to do some weird bodily contortions to get the sword all the way out. Even with a shorter blade, it’s going to take you a lot longer to draw the sword from your back than it would if it was on your hip. Not to mention, returning the sword to the scabbard is going to be a real bitch if you can’t, you know, see the scabbard. I see many unfortunate heroes dying from self-inflicted stab wounds to the top of their heads.

The fix: Honestly, including back scabbards in fantasy fiction is a pretty minor sin, all things considered. They do look pretty damn cool. But if you want to be more realistic, there’s some evidence that big two-handed swords were carried on the back to transport them from place to place, but they were probably discarded before battle began. So, if you use back scabbards like that, you’re within the bounds of reasonable historical use.

3) Armor works.

Oh, man, this is a big one for me. Yes, armor works, and it works really, really well. So well, in fact, that most swords are useless against good armor unless used in very specific ways (half-swording, for example). Blades just don’t cut through metal (generally), and that means someone in chain mail or plate armor was pretty well protected from sword blows. Armor became so good that a bunch of specialized weapons developed to defeat it, mostly polearms that put a lot of pressure on a very small area, puncturing or crushing rather than cutting.

There are tons of videos on YouTube demonstrating the resilience of metal armor (and even padded armor) against sword blows, but here’s a couple of great videos on the subject from Falchion Archaeology to get you started:

Cluny Falchion vs Maille – This an excellent cutting test with a falchion, a sword known for its fearsome cutting power, against padded armor and chain mail. He doesn’t test the falchion on plate because it’s kind of a foregone conclusion.

Polearm Test 1 – Want to see what types of weapons could actually defeat plate armor? Here are some great examples.

The fix: This is a tough one because sometimes you need the hero to cut through a bunch of mooks without describing every little detail. I’d say it would be enough to show armor working from time to time for both heroes and bad guys. You might also show the hero using half-swording and other techniques designed to defeat armor (and maybe stating that’s what they’re doing). Or, hell, dispense with the every-hero-must-have-a-sword trope and give you’re protagonist a poleaxe because they know they’re going to be fighting dudes in armor.

4) Shields are also really, really good.

You rarely see a hero with a shield. Why is that? Trust me, the ability to places a small, mobile wall between you and a guy trying to hit you is awfully handy. There’s a reason the shield is so ubiquitous throughout history—it works. That said, the personal shield was largely abandoned once plate armor became the norm because it was kind of redundant at that point, and you had a better chance of defeating the other guy’s armor with a two-handed weapon, like a poleaxe (see point three).

The fix: Use them where appropriate, and like armor, show them being effective once in a while. Shields were used offensively too, so there’s a lot of cool opportunities to let the hero use her shield to knock bad guys off their feet or smash their faces in.

5) Fewer instant kills.

In movies, you often see the bad guy take a single cut from the hero’s sword (slicing through armor like it was made of tissue paper) and then fall down stone dead. The truth is that most deaths on a medieval battlefields were probably from blood loss and infection rather than instantly fatal wounds. Humans are actually kind of hard to kill, and unless you inflict a really catastrophic wound, like behead someone or crush their skull, instant death is unlikely. That means even a mortal blow leaves the bad guy quite a bit of time to do some damage. It’s why historical European martial arts teach continued defensive measures AFTER a telling blow is struck. Basically, you want to stick your opponent and then get out of the way while he bleeds to death.

If you’d like to read a very thorough and engaging article on this subject, “The Dubious Quick Kill” by Frank Lurz is about as good as it gets.

The fix: Another tough one because you don’t want every bad guy lingering around after the hero has effectively defeated him. Your hero is special, and she should be able to kill the bad guys in a single blow now and then. That said, it’s pretty simple to get the idea across by dropping it in occasionally. Have your hero strike a mortal blow and then continue to defend himself as the bad guy slowly bleeds out. Show the aftermath of a battle where some men have died from blood loss and infection rather than skulls cloven to the teeth and such (not that that didn’t happen every once in a while). Also, it never hurts to do a little research on wound trauma for this kind of thing; the more you know how the body works (and what stops it from working), the more realistic you can make your fight scenes and any resulting wounds.

Of course, there are lots more melee myths out there, and I may explore some in future posts, but these five are a good place to start. If you have any experience in this area and want to share some of your own melee myths (or point out something I’ve missed), please do so in the comments.